TDEE, BMR, RMR, NEAT, EAT, TEA, & TEF

Let's talk thermodynamics, energy balance, and all of these acronyms

Breaking down energy expenditure can get confusing and everyone’s numbers are different depending on their daily activity, the physical demands of their jobs, how often and what kind of exercise they partake in, and so much more. In this newsletter, I will try to explain it in simple terms so it makes more sense and doesn’t seem like such a daunting task to figure out for yourself.

The concept of energy balance follows the notion that energy intake should be matched to energy expenditure, or there will be changes to the mass. Energy balance is the result of the First Law of Thermodynamics which states that all energy taken into the body is accounted for is either utilized directly, stored, or transformed to kinetic energy or heat.

The First Law of Thermodynamics, also known as the law of conservation of energy, states energy can be transformed from one form to another, but cannot be created nor destroyed. When applying this context to nutrition, calories are either used to produce energy, used to sustain life, given off as heat, or stored for later use.

TDEE

Total Daily Energy Expenditure. Sometimes referred to as Total Energy Expenditure (TEE). This is the amount of energy (calories) spent in a typical day. TDEE is comprised of three main components: BMR, TEA, and TEF. NEAT is considered an aspect of TEA.

One of the most common ways to calculate TDEE is to estimate your RMR, then multiply your RMR by an appropriate activity factor.

Weight (lbs) x 10 = RMR

RMR x activity factor = TDEE

Activity factors:

1.2-1.3 = very light

1.5-1.6 = low active

1.6-1.7 = active

1.9-2.1 = heavy

Very light refers to office work, driving, and no vigorous activity.

Low active refers to 30 minutes of moderate activity. This is most office workers with additional planned activity.

Active refers to an additional 3 hours of activity such as riding a bike 10-12 miles in an hour or walking 4.5 miles in an hour

Heavy refers to vigorous activity such as physical labor, full-time athletes, and steel or road workers.

It’s important to note that even the most commonly used formulas can have up to a 20% variance in overestimating or underestimating resting metabolism and TDEE.

BMR

Basal Metabolic Rate. Achieved at steady state. The rate at which a living being gives off heat at complete rest. BMR and RMR are often used interchangeably but BMR is different. BMR is measured using stricter conditions while RMR is measured under looser conditions. BMR is the term used when measurements are taken after a subject had spent the night in a metabolic ward or chamber, has fasted for 12 hours, and slept at least 8 hours. RMR is measured after the subject spends the night at their own home and is driven to a lab for measurement.

There are four equations you can use to determine your BMR. There are pros and cons to each.

Harris-Benedict Equation

Pros: Simple and easy to use. Does not require body composition data.

Cons: Least accurate. Does not account for body composition.

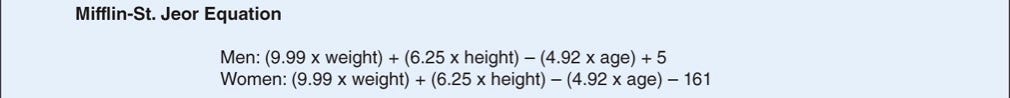

Mifflin–St. Jeor Equation

Pros: Simple and easy to use. Does not require body composition data.

Cons: Does not account for body composition. Not as accurate as the Katch-McArdle equation.

Katch–McArdle Equation

LBM = Lean body mass in kg

Pros: Accounts for body composition. Is more accurate than the Harris-Benedict and Mifflin-St. Jeor equations.

Cons: Requires precise body-composition tests and data. Does not provide substantially more accurate data for real-world applications.

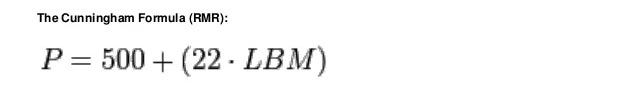

Cunningham Equation

LBM = Lean body mass in kg

Pros: Accounts for body composition. Is more accurate than the Harris-Benedict and Mifflin-St. Jeor equations.

Cons: Requires precise body-composition tests and data. Does not provide substantially more accurate data for real-world applications. Is more likely to overestimate than the Katch-McArdle equation.

RMR

Resting Metabolic Rate. Measured at rest and represents the minimal amount of energy required to sustain vital bodily functions (respiration, blood circulation, and temperature regulation). RMR accounts for approximately 70% of TDEE.

Chronic or acute illnesses and hormonal changes and certain medications can influence RMR. Thyroid hormones and diabetes are common conditions to name a few.

In order to avoid a decline in resting metabolism, individuals are encouraged to avoid starvation diets that could lead to the wasting of skeletal muscle and instead be encouraged to build and maintain muscle. Maintaining muscle mass is particularly important during aging because it’s been shown that some of the decline in RMR associated with getting older is caused by a decline in muscle.

NEAT

Non-exercise Activity Thermogenesis. Energy expended doing (mostly) unplanned exercise. This includes but is not limited to: brushing your teeth, cooking food, folding laundry, mowing the lawn, and fidgeting.1

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)

EAT

Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. Energy expended during physical activity. Accounts for approximately 20% of TDEE. Physical activity can be influenced more dramatically than RMR and TEF which for the most part stay relatively constant.

TEA

Thermic Effect of Activity. Sometimes referred to as Thermic Effect of Exercise (TEE). Energy expended during physical work, muscular activity, as well as planned and structured exercise. TEA accounts for the most variability of daily energy expenditure. TEA can further be broken down into NEAT and EAT as I explained above.

TEF

Thermic Effect of Feeding. Energy expended by processing food aka digestion. TEF typically accounts for 6-10% TDEE.

When you consume food, your body uses energy to digest it and transport the nutrients from your gut to your blood and the rest of your body. Studies show that TEF can be increased by consuming larger meals (as opposed to smaller meals), intake of carbohydrates and proteins (as opposed to dietary fat), and a low-fat plant-based diet.2

The Thermic Effect of Food: A Review

People often hear these acronyms and have no idea where they fit into their own goals. Figuring out your own numbers and applying that information to a nutrition plan is exactly what certified nutrition coaches like myself can help you with! I wanted to break down each one and explain its purpose.

Hopefully, this article made it easier to understand and gave you the tools you needed if you were interested in calculating your own TDEE. In later newsletters, I will dive deeper into macronutrients that make up certain percentages of your TDEE.

Remember; everyone’s lifestyle, metabolism, and body composition are not going to be the same. That’s why it’s important to calculate and understand your own numbers so you can make a plan to reach your goals and execute them!

Levine JA. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Dec;16(4):679-702. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0227. PMID: 12468415.

Calcagno M, Kahleova H, Alwarith J, Burgess NN, Flores RA, Busta ML, Barnard ND. The Thermic Effect of Food: A Review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019 Aug;38(6):547-551. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1552544. Epub 2019 Apr 25. PMID: 31021710.

Very informative. Thank you!